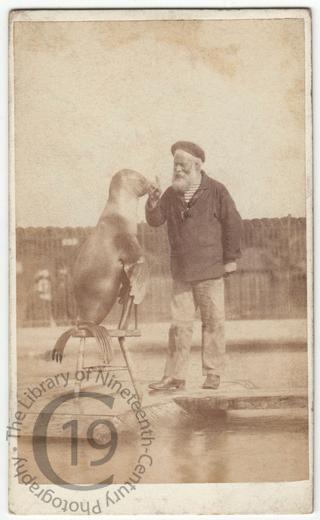

François Lecomte

A carte-de-visite portrait of François Lecomte, who was for many years the keeper of the seals and sea lions in London’s Zoological Gardens. Various newspapers reported that he had died ‘a few days ago in an obscure lodging in Frederick-street, Portland town,' a district of London lying just north of the northwest corner of Regent’s Park.

‘Visitors to the Zoological Gardens will miss a well-known face – that of the old Frenchman at the seal-pond, who used to put the sea-lion through its tricks and induce it to jump suddenly into the water and plentifully besprinkle the unwary. François Lecomte died last week, and the love of his pets was so strong to the last that he begged to be carried to the Gardens, declaring his “children” would die without him, and he should get better if he could but see them. He was accordingly taken out in a chair, but he was too weak to bear the fatigue, and was carried home to die. The Prince of Wales, who frequently used to have a chat with him on Sunday afternoons, visited him before his death’ (The Graphic 28 January 1877).

‘François was an old man-of-war’s man in the French navy, and subsequently attached himself to whaling expeditions, in the course of which he became familiar with the manners and customs of the seal and the walrus. Many years ago he entered the service of the society, and at once began to train the animals to perform a number of amusing tricks. He was a guileless old man, who loved to talk of his adventures, and who made it his pride to win the affection of the animals under his care. They knew his voice and his whistle, and instantly obeyed him. […] He was a great favourite with the Prince of Wales, who invariably sought him out on his visits to the gardens with the Princess and their children and had long gossips with him about his experiences afloat. Nothing delighted the old man more than to be thus accosted in his native tongue, and on such occasions it was his custom to summon his “children” (as he called them), and make them go through their performance, to the infinite delight of the Royal children. He died a few days ago of disease of the throat, and the Prince of Wales showed his solicitude for his humble friend by calling to see him at the last’ (Belfast News-Letter, 26 January 1877, quoting an article that had appeared in The Globe.)

According to another report, ‘He had fallen into ill-health, being taken with a severe attack of bronchitis, owing to the constant exposure and damp which his work necessitated, and it is distressing to hear that for some weeks he suffered from extreme want. When his condition became known help immediately flowed into him. Unfortunately it came too late. […] It remains to be seen who will be appointed as the old man’s successor. Whoever may be selected, it will be long before he will be able to supply Lecomte’s place. The genial old Frenchman had made seals and sea-lions a study. His animals knew him, would fawn about him like hounds, would answer his slightest word, and obey the least motion of his hand. He had, indeed, almost a genius for managing and taming the phochine [sic] tribe. The temper of seals is proverbially bad’ (Royal Cornwall Gazette, 2 February 1877, reprinting an article that had earlier appeared in the Telegraph.)

When one of the sea-lions died in 1896, several newspapers mentioned Lecomte as the man who had first brought a sea-lion to London. When that first animal died only a year later, Lecomte had been sent out the Falkland Islands in 1866 to secure fresh specimens. He had apparently set out on the return journey from Port Stanley with four but only one had reached London alive.

Photographer unidentified.

Code: 127464