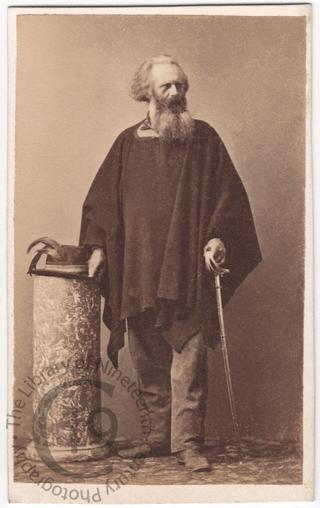

John Whitehead Peard

A carte-de-visite portrait of John Whitehead Peard (1811-1880), known as ‘Garibaldi’s Englishman’ and ‘Il Garibaldino inglese.’ He accompanied Garibaldi through several of his campaigns and was warmly thanked for his services by the Italian general, though his motives caused some controversy in his own homeland.

Born at Fowey in Cornwall in 1811, Peard was the second son of Vice-Admiral Shuldham Peard. Educated at Exeter College, Oxford, he was called to the bar at the Inner Temple in 1837 and for some time practised on the Western Circuit.

‘Colonel Pear held a captain’s commission in the Duke of Cornwall’s Rangers when the Italian war of Independence broke out in 1859, and at once offered himself as a volunteer to Garibaldi. He shared the adventures of “the Liberator of Italy” during several campaigns, and more especially that of 1860, when he obtained the warm thanks of his commander’ (Southend Standard, 26 November 1880).

‘Serving in the Italian army, 1859-60, he distinguished himself at the battle of Melazzo, 20th July, 1860. Victor Emmanuel gave him the cross of the Order for Valour, and Garibaldi visited him at Penquite [his manor in Cornwall], April 25th, 1864. Settling down near his native place he […] was sheriff of Cornwall in 1869. He died in 1880 and was buried at Fowey’ (The Cornishman, 26 May 1898).

To this day, his marble bust still stands among the monuments to Italian patriots on the Janiculum in Rome.

His participation in the war was, however, not without controversy. In 1859 it was widely reported that he was only in Italy for what he saw as the ‘sport’ of killing other human beings, and was wholly unconcerned on whose side he fought. Peard encountered a Special Correspondent for The Times at a hotel in Turin, ‘where he announced to me his intention to have some sport with the Alpine chasseurs, and asked for direction as to Garibaldi’s whereabouts. He is a man of near 60, of a tall and colossal frame, imperfectly acquainted with the language, and ignorant of most Italian matters. He professes, I am told, the utmost indifference to the cause he serves. Between him and his fellow combatants there is hardly any intercourse. Garibaldi allowed him to follow his camp. He makes war at his own expense and encamps apart from the corps. He receives no orders, asks for no information as to Garibaldi’s movements. He is indefatigable in the march, intrepid in the fight. Garibaldi numbers 50, or perhaps 100, of the best marksmen in Europe, but the Englishman is the deadliest shot. […] He is never wanting in the hour of strife; he takes his place in some hidden nook, all alone, aloof from the rest, squatted on the ground, calm and impassionate, taking leisurely aim, like a sportsman awaiting a lion or wild boar at the brook. He has a double-barrelled rifle, a sabre, but no bayonet, and takes no part in the melee when the Garibaldini come to close quarters. Some people told him he must be very strongly devoted to the Italian cause to come out in arms in its support at his time of life. He answered, with a yawn, he was very fond of shooting, and must take part either on one side or the other’ (The Times, 26 July 1859).

This report, which didn’t actually name Peard, caused quite a stir and was widely reprinted in the British press. A few weeks late, a correspondent for the Daily News named him and reported that ‘It seems his only object was that of getting a good shot at the enemy, and whenever he killed an Austrian he was seen to mark him down in his pocket-book. A few days ago I met Captain Peard at Brescia, and he was kind enough to show me his book, from which it was apparent that twenty-five Austrians were killed by him during the campaign, besides ten who were under the heading of “uncertain.” I was greatly amused at the unpretending manner in which our countryman spoke of his rather curious propensity for such murderous game, for he assured me he professes the utmost indifference to the cause of Italian independence. Such is Capt. Peard, who is now anxious that war should begin on the Arno or on the Tevere, in order to have a few score of Swiss soldiers to add to his list, under the heading of “really dead.”’ (Reprinted in The Globe, 12 August 1859).

Numerous reports and indignant letters appeared condemning Peard’s ‘monstrous savagery’ but it should be pointed out that Peard vociferously denied the allegations levelled against him. He repudiated the latter report as a ‘gross and wilful falsehood’ and denied the existence of the putative notebook in which he supposedly kept his murderous tally, asserting that ‘I have never expressed any feeling but one of devotion to the cause of suffering Italy.’ (His letter originally appeared in the Plymouth and Devonport Journal; reprinted in The Globe, 16 September 1859, and in numerous other newspapers).

Nevertheless, naval officer C. N. Forbes still described him as ‘a bloodthirsty man, who, unable to gratify his penchant for murders in his own country, comes out here and gloats over his victims’ in his history of the recent conflict, The Campaign of Garibaldi in the Two Sicilies, published in 1861.

That Christmas there was even a farce titled Garibaldi’s Englishman at the Royal St James’s Theatre. Its thin plot revolved around the attempts of a commercial traveller for a pickling manufacturer to pass himself off as the celebrated rifleman.

Photographed by Grillet of Naples.

Code: 127520