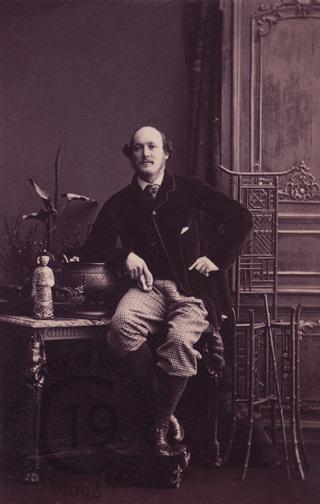

Captain George Longley (1836-1892)

Captain George Longley joined the Royal Engineers as an Ensign on 21 December 1853. ‘Major Longley served with the local rank of Captain in the Turkish Contingent Engineers in 1855-56 for which he has the Turkish Medal. Served with the expeditionary force in China in 1857-59, and was present at the capture of Canton, affair at the White Cloud Mountains, capture of Namtow, attack on the Peiho forts,-dangerously wounded (mentioned in despatches on all the above occasions and Brevet of Major).’

From the Times (Friday 14 October 1859), an article titled ‘The Affair of the Peiho’. The article shows Captain Longley in rather a good light and since his words also explain Silvy’s use of the Chinese props seen in this portrait, the article is given here in full:

The Bishop Auckland Herald contains an account of a public welcome given to Captain Longley, R.E., son of the Bishop of Durham, on his arrival in Bishop Auckland. An address of congratulation having been presented to Captain Longley the gallant captain in acknowledging it said – “It is with feelings of sincere gratification that I return you my thanks for the address which you have presented to me. I have, as you say, been a long distance from home. It was in October, 1857, that I was ordered to India, with my company, but on our arrival overland at Point De Galle our destination was changed to China. I arrived there in time to take part in the action at Canton, under General Straubenzie [sic], after which I had the honour to be named aide-de-camp to the General. I was present at the affair at the White Cloud Mountains and capture of Namtow, and remained at Canton till the arrival of his excellency the Hon. F. Bruce, Her Majesty’s Plenipotentiary, and Admiral Hope. In June we left Canton for Peiho, under Admiral Hope, who we expected would go direct to Pekin to ratify the treaty which had been made. We found, as you know, that the passage up the river was stopped by a strong barrier, and the forts which had been taken last year rebuilt. Of course we were not able to ascend the river. Mr Bruce and N. Bourbonnel, the French Ambassador then placed the matter in the Admiral’s hands, and an attempt was made to pass the barrier, the result of which is already known to you. My company was distributed among the gunboats, and I, with 10 men, was on board the Plover, where we acted as sharp shooters. On the order being given, I went ashore with the landing party, and was in the act of carrying the scaling ladders through the mud when I was unfortunately wounded. I remained two hours with my men, and then returned on board to get my wound dressed. It is not for me to criticize the acts of my superior officer; there is an oriental proverb which says ‘Speech is as silver; but Silence is as gold,’ and the Admiral is much my senior that it would not become me, and I am sure you will excuse my going any further into the matter. There is one expression, however, in your address which I would like to correct if you will allow me, and that is as to the ‘treacherous Chinese.’ I don’t think we have any right to accuse them of treachery, because, when Mr Bruce made his appearance, they told him to go up by another way which was open; but for certain reason - perhaps he thought it was not consistent with the honour of his country – he thought it better to attempt to force the passage; but they certainly did offer to let him go up the other way, and therefore there perhaps may be some excuse for them. They certainly did not fire the first shot, for it was not until after Captain Willis, the Admiral’s flag captain, had blown up the first barrier, which was tantamount to a declaration of war by us, that they fired upon him, and he retired. Next morning the gunboats were ordered to take up their positions at 7 o’clock, but on account of the strong tide and the wind this could not be effected until 2 o’clock in the afternoon; and during the whole of this time the Chinese never fired a shot. Had they opened fire during this interval when the gunboats were aground, I don’t think one of them would have escaped; but they waited until the Admiral had pulled up the first row of stakes and gone towards the second before they fired upon us. Therefore I don’t think we can call them treacherous Chinese, Then, as to the report which stated that there was trap laid for us – this is entirely incorrect – there was no trap at all. We saw it all before we went; we saw the masks before the embrasures, and of course concluded that there were guns behind them, and we saw the mud we had to cross. Therefore I hope you will hear no about the traps or treacherous Chinese. Then as to our forcing civilization upon these barbarians, as we term them, it seems to me to resemble such a case as this. A crusty old gentleman lives in Bishop Auckland, who likes to follow his own crochets and keep within his house; but a number of persons meet together, go to him, and say, ‘You must come out and be civilized; or, you must let us into your house, and become a Christian.’ No I think that man has a right to defend his own house the best way he can; every man’s house is his castle, at least it is acknowledged to be so in England, and I don’t know why it should not be so in China. I don’t say that we are to give up our trade if we can help it, but I don’t think we are right in forcing our civilization upon China; I don’t think we show them very good customs that they need wish to imitate them and it is a fact, as stated by Lord Elgin, that the further he went into the interior the better disposed the people were toward us; but at Canton and other places, where we have been established for 200 years, they have very bad feelings towards us, because they have had much injustice done to them. As to the part I have played in the late affair, I don’t think I have done any more than my duty. My wound is now healed, and the surgeons say I may take any exercise I like; but had it not been for my good constitution I probably should not have recovered. I have to thank you, not only for the kind manner in which you have spoken of me, but also for the terms in which you have mentioned my father. I am gratified to think that he has succeeded in gaining your regard and respect during the short time he has been among you.” [Captain Longley’s father, Charles Thomas Longley became Bishop of Durham in 1856. He was subsequently Archbishop of York 1860-1862 and Archbishop of Canterbury from 1862 until his death in 1868.]

On 27 May 1875, Longley’s name again appeared in the Times, sadly this time as a bankrupt. Described as ‘late of 60, Prince’s Gate, then of Devonshire Lodge, Maidenhead, and elsewhere, Lieutenant-Colonel in the Royal Engineers on half-pay’, a statement of his affairs disclosed debts of £11,375, with assets of £1,756.

The 1891 census shows him living at 4, Westbourne Terrace, Portsea. He gave his profession as ‘Retired Colonel Army.’ According to the census, he was married, but there is no sign Mrs Longley, at least on the night of the census.

Colonel George Longley died, aged 56, on 10 January 1892 at Portsea, Hampshire.

Photographed by Camille Silvy of London on 30 January 1861.

Code: 123861